What is the future of the Jewish people and Jewish identity as we advance into the 21st century? What unites us as a people? What changes will we need to make socially, psychologically, and religiously to adapt to the challenges that this century will bring? Tsvi Bisk has some answers.

This is the fifth post in the Bronfman Big Idea Series.

About the Author

Tsvi Bisk is the director of the Center for Strategic Futurist Thinking and the author of a new book, The Optimistic Jew: A Positive Vision for the Jewish People in the 21st Century, as well as Futurizing the Jews: Alternative Futures for Meaningful Existence in the 21st Century.

Tsvi is also this week’s featured guest on Ha’aretz’s Rosner’s Domain, where he answers questions about Jewish identity and continuity. After reading his proposal here, head over and check it out.

Covenant with the Future by Tsvi Bisk

Rationale

Two polls have justifiably alarmed the Jewish people.

- In Israel, about 50% of young people polled identified themselves as primarily Israeli rather than Jewish

- In the United States, close to 50% of Jews under the age of 35 indicated that they would not view the destruction of Israel as a personal tragedy

These two indicators taken together cast doubt on the very future of the Jewish people. This being the case the formulation of concepts and practical programs dealing with how Jewish life might look in the future must be our top priority.

The project I envision– Covenant with the Future– will attempt to do just that. That Jews need a covenant with their future if we wish to survive and flourish. We must “futurize” Jewish civilization and in order to do that we must “futurize” Jewish thinking.

The working assumptions of this proposal are that:

- The Jewish past and Jewish tradition are no longer identifying elements of Jewish identity and might even be divisive for ever-growing numbers of young Jews in Israel and other communities around the world

- Two objective trends are serving to exacerbate Jewish identity: globalization and ever increasing rates of change (where real time change constantly erodes the unifying force of tradition)

- Only visions of a common Jewish future can be a unifying force– visions that contain practical projects (modern mitzvot) that enable young Jews from every part of the Jewish identity spectrum to work together on projects that have universal human consequences, but are yet unframed within a Jewish value system. This would be our Covenant with the Future

The Challenge: Judaism– From Civilization to Space Age Civilization

By the end of the 21st century, it is probable that humanity will have explored the entire solar system either directly or by robotics. Small scientific outposts will probably have been established on various planets and moons on larger planets. Substantial portions of human economic activity– from mineral extraction to tourism to new methods of generating energy– will have become extra-terrestrial.

If historical precedent is any indicator, we must assume that a disproportionate number of Jewish individuals will participate in these developments.

This transformation of human life– from being limited to the crust of the planet earth to being integrated into the entire solar system as its new “natural” environment– will have profound cultural, psychological, and spiritual consequences. Every legacy civilization, religion, philosophical system will be challenged as never before by this new reality. Some will adapt, integrate into and contribute to its development. Others will fail and pass from history.

What will be the fate of the Jews? How will we adapt? What survival strategies must we develop– socially, economically, politically, and spiritually? What will it mean to be Jewish as human civilization begins to settle and explore our solar system?

Why should one even care about the continuation of the Jews as a civilization? What will this new Jewish civilization contribute to humanity– to the Jews? Can it even contribute to the Jews if it does not first contribute to humanity? What will be the interim stages and how will they be manifested?

We can rise to this challenge through an “imagineered” overview of possible futures of human history and the place of the Jews in those possible futures by applying with the most stringent standards of futurist and policy making research. It will be informed by Mordechai Kaplan’s approach of Judaism as a civilization coming to terms with the new human reality being created in the 21st century.

Creating a Unifying Meta-Identity in the 21st Century

The project will relate to Judaism as a practical life system rather than an abstract theology. On the basis of the above-mentioned future analyses, it will suggest practical strategies and mitzvot for living in the new emerging global reality. It will be an attempt to formulate a unifying meta-identity for an increasingly diverse Jewry on the background of ever growing identity differentiation.

Sixty years ago you might have lived in New York, Paris, Tel Aviv, London, Buenos Aires, or Antwerp, but you or your parents were from Pinsk or Warsaw or…! And even if you weren’t, when you met Sephardic or Yemenite Jews, you had enough knowledge of synagogue procedure and Jewish tradition to develop mutual empathy.

In Israel today, what do Ethiopian, Haredi, Russian Jews, and 3rd generation kibbutz sabras and development town residents have in common? In the Diaspora, what do Jews from Argentina, San Francisco, and Paris have in common? What do agnostic Jews have in common with the Haredim? What is the force unifying gay Jews, children of “Yordim” [Israelis living outside Israel], and Jewish children of mixed marriages, such as the 45% of those on college campuses who still identify as Jews?

I believe that only inspiring visions of the future can provide the unifying bond of Jewish identity. Like Zionism in the first decades of Israel’s existence, these visions must be capable of uniting the varied and diverse elements of the Jewish people around practical/actionable projects to create a new sense of Jewish citizenship that spans the globe.

Such projects must coincide with world trends and contribute to all of humanity. They must be concrete, doable projects, each of which alone can have a transformative potential, and each of which alone could justify this proposal.

Fixing the Present Situation is Not Enough

Mordechai Kaplan’s approach had significant influence on the course of Jewish history in the 20th century. But it was facilitated by two objective historical realities:

- The reality of America’s dynamic non-sectarian civil society which after World War II almost compelled inter-ethnic and inter-religious cooperation. This essentially forced the intra-ethnic and intra-religious cooperation of the Jewish people

- The unifying project of developing Israel, which after the Holocaust became of almost transcendent importance to the vast majority of the Jewish people

These two historical realities– intra-Jewish group cooperation and Israel as a unifying force– are in an advanced stage of erosion in the first decade of the 21st century.

Israel has become increasingly divided internally (for both religious and political reasons) and this is reflected in growing divisions with the Diaspora (both in regards to feelings about Israel as well as their own internal divisions).

American society is more divided than at any time since the end of the Jim Crow era. This divisiveness has divided the Jewish intellectual class into neo-cons[ervatives] and traditional liberals. This divisiveness along with evangelical support for the right wing in Israel has contributed to the erosion of traditional liberal Jewish support for Israel (as militant evangelicalism has become a major player in American divisiveness in general).

As a consequence, Israel is no longer a unifying force for growing numbers of young Diaspora Jews. And given the internal divisions within Israel regarding Haredi entitlements and the settlements it is less and less a unifying force for itself.

There is also a growing generational differentiation regarding the Holocaust. Within the next 10 years, the last survivor and the last murderer will have died. The Holocaust will increasingly become a symbolic event like the Exodus from Egypt or the Inquisition and expulsion from Spain.

Its gut wrenching immediacy will fade. Generations will arise “who knew not one survivor.” As with Israel, Holocaust remembrance will not have the unifying power it once had.

Products of this Project

In light of all of the above, the Covenant with the Future would be a multi-dimensional project with the following objectives:

- Design possible models of Futures Studies to be introduced into existing Jewish Studies Programs and make it a core theme of Jewish policy making it a core theme of Jewish policy making. One of the great ironies of modern Jewish life is that some of the foremost pioneers of futurology were Jews– Kahn, Toffler, Polak, and others– yet futures thinking has not penetrated Jewish policy making. This is despite the fact that Zionism was the quintessential futurist political/cultural movement. Herzl’s The Jewish State and Old New Land were futurist scenarios. Ben Gurion, Weizmann, Jabotinsky, and Rabbi Bar Ilan were all “futurists” in that the full force of their intellect adn imagination were focused on the future. Yet in recent years, we seem to have turned our back on the future

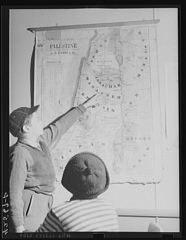

- Design a new model of interaction between Israel and non-Israeli Jewish communities. What I call multi-node interactions, as opposed to the two node concept of Israel-Diaspora– a multiplicity of Jewish centers (not Diasporas) interacting across a global network of constructive Jewish activity

- Develop a menu of Jewish/universal projects that take the concept of leveraging from the private sector– what I have termed multi-dimensional/multi-purpose projects. The Jewish Energy Project (described in a chapter of my recent book, The Optimistic Jew, as well as several articles) would be an example of this. These national-universal projects should be “sold” as modern manifestations of the biblical injunction to be a “Light Unto the Gentiles”

- NOTE: To learn more about this concept, read: “Guest Author Tsvi Bisk Asks, ‘What if One Billion Dollars a Year Were Used to Buy Israeli Alternative Energy Technology?'”

- Such projects would strive to involve previously disinterested Jews in Jewish activity and to serve as a platform for cooperation with non-Jewish groups, including ones that are at present not friendly to Israel or to the organized Jewish community. Here I would try to formulate pilot projects during my two-year tenure using Brandeis students and faculty as starting points. The aim would be to reconstruct ground-up movements (much like the Committees of Correspondence during the Revolutionary War– but this time based on the internet)

- Mining the tradition: searching the sources for those nuggets of wisdom that implicitly contain some of the building blocks of our new “imagineered” future– or which could be so reinterpreted by the imaginative mind, perhaps even sowing the seeds of a “Philosophy of Jewish Futurism,” derived as much as possible from the Jewish tradition

- A practical strategy of how current Jewish organizations (legacy and internet-based) can help construct a new futures oriented reality and develop a cadre of Jewish futurists to develop and expand the field through the “fan effect”

- All of the above elements will appear as parts or chapters of the final product, a book entitled Covenant with the Future

Target Audiences

- Young– from hi-tech to new age to atheistic to religious– Israeli and Diaspora alike

- Jewish organizations and policy makers

- The new “under the radar” virtual Jewish communities and alternative Jewish organizations

- Disaffected Jews on college and university campuses

Just as Birthright celebrates and encourages an appreciation of the Jewish past, so will Covenant with the Future strive to stimulate enthusiasm for potential Jewish futures. Without positive visions for our future, we wander blindly– with our past as a burden rather than an inspiration.

Your Contribution

So what do you think of these ideas? Are they valuable? How could these plans be further developed to meet your needs more fully? What are your reactions and thoughts?

We can’t wait to hear your comments.

Credit

Images sourced from PingNews.com (Herzl image from here), with thanks.

Subscribe

![]()

Like what you are reading? Please subscribe by e-mail or feed reader by clicking the sidebar icons.

[…] “Covenant with the Future” by Tsvi Bisk, Director of the Center for Strategic Futurist Thinking– UDPATED! Read the post here […]

What did I just read? After getting through all the text I cannot understand what the heck the idea is. I might be missing something.

I saw an idea, I think, but not a plan, or a concrete proposal.

Not trying to be mean, just honest.

I’ve got quite a bit to say about this submission, but little time to say it all – so I’ll start with an observation that this submission presumes a definition of “Jewish Community” that should be stated more clearly, as it’s clearly not the same definition that existed in the past and doesn’t pretend to be. But I’d like to know just the same how it’s defined for this submission.

The definition will seem to be difficult to come by, because to any degree that it differs from the previous definitions, it can be said to be “something else”. As radical as some of Mordechai Kaplan’s ideas were, his view was evolutionary, not revolutionary – and he would probabloy have seen definitions as descriptive, not prescriptive or futuristic. So, the comparisons between what is being proposed and Kaplan’s view should be explored further.

One model to use to explain by comparison what the problem in defining Jewish communithy here would be the same in describing Jewish art. What is Jewish? What is art? What is Jewish art? The person who makes it is Jewish? The art has Jewish content? It has both? It was made in Israel? What?

Same here with Jewish communities – the essence of any solution should be to find soemthing that allows us to maintain Jewish community, and our individual identities with it. There is a belief implicit here that merely acting in common, though few of us may share the basic reasons for our common action, unite us as a community. My own opinion is that this is false. An example is the Vietnam War Movement. Some opposed the war believing that war, all war, is evil. Others supported it because they didn’t want to fight for any war and risk their lives. To look at them, at the demonstrations, you’d see no difference. But the quality and sustainability of their “community-ness” is evident in that as a community they disbanded when the cause (war) for that community disbanded. Once their objective was achieved, they had nothing holding them together any longer.

To sustain Jewish communities it’s important to have causes to rally around – I don’t dispute that. We have to do things that are acts on the ground, I don’t dispute that either and neither has tradition for at least the last couple thousand years. But the quality and sustainability of community rests on a foundation of common ideals. To call our ideas “universal” is fine – but it sustains the community of man. It doesn’t sustain the Jewish community unless there’s something Jewish about it, and if this submission has something Jewish about it in a particularistic sense, it’s subtle and probably meant to be so because it seems that the author believes particularism to be devisive.

To use the comparison, it seems that the essence of Jewish community is like Jewish art for those who define Jewish art as art made by Jews, even when there is no especially Jewish content in it. My question is then, how can this vision of Jewish society achieve the promise of Jewish community?

To clarify, what I meant when i said that “the quality and sustainability of commnity rests on a foundation of common ideals”, what I was saying is that we achieve merely the utilitarian function of what we do, the “result” of what we do when we work on common acts together. This has no small value, but it doesn’t create “community”. Community is created when we do common acts, but our ideals about the value of the goal we seek to achieve is held in common. We may achieve that goal a thousand different ways, but that we all sought to achieve the goal is what unites us into a community.

To “Huh?”

I do not moderate comments in my journal but I expect you to be respectful to me, guest authors, and other commenters in order to create interesting and meaningful discussion.

The Bronfman contest, and subsequently the title of this series, is about big ideas. Of course practical, actionable steps should be involved, but we also need to really think about our thinking and the assumptions we are making about Jewish community and identity. This proposal takes us there.

Perhaps you can rephrase your comments into a question that we could try to answer. Are there some parts of the proposal that you agree or disagree with? Are there valuable ideas here? What parts of the proposal have the most meaning and what could be changed to improve it?

I welcome your thoughts.

Maya

Shai said: “My question is then, how can this vision of Jewish society achieve the promise of Jewish community?”

Good comment, thanks, Shai. We are finding it really hard to get at the marrow of this question. As you can see, we are all poking at it, hoping the angle is right or agreeing to take a particular tack that we feel is a good approach, although we’re not sure what the best one would be.

Fortunately, Judaism teaches us the the best answers are found once we truly refine and figure out the best way to ask something. I appreciate your efforts to push us down that road.

Maya

[…] I met with Tsvi Bisk of the Center for Strategic Futurist Thinking and Jonathan Shapira of the Cleantech Investing in […]

I enjoyed reading Mr. Bisk’s submission to the contest. The future oriented outlook of this project seems to contrast nicely with Shai’s project, which has a major component of focusing on Jewish history. Learning from the past, and looking towards the future are both important, in my opinion. The judges have a hard decision on their hands.

Thanks for another great entry Maya. I hope all is well.

Did Wyman contact you about the Vilnius Jewish Library yet? I finally got in touch with him. We are thinking about holding some book drives in major U.S. Jewish communities, and hopefully some people will write articles encouraging people to send books. Any ideas on how to make international shipping costs as low as possible, or how to get some donations to decrease the cost of sending a large amount of books overseas? Please let me know if you think of anything.

Agreed, the two proposals in particular complement each other nicely.

No word from Wyman. Did you get a chance to see my comment on the Vilnius Jewish Library blog yesterday?

As for shipping costs, I definitely think it’s a good idea to get in touch with someone from the National Yiddish Book Center and develop a contact there on these kinds of issues. If Wyman is still there, he may want to try and get in touch with local bookstore owners/managers and see what they suggest, as I’m not sure what resources are specifically available there.

Maya

Hey Maya,

Just got your comment and posted it. Great suggestions. I really like the Amazon wish list idea.

I have to think about your comment concerning the cost of shipping versus the value of the books. You make a good point that it might be cheaper to purchase books locally. However, I don’t think there are many of those books around Vilnius, so I’m not sure what to do. Any ideas?

I think that Wyman is somewhere in Europe now, and he will be in Vilnius in a couple weeks. I will talk to him about contacting the NYBC.

I’m surprised Wyman hasn’t contacted you. He asked me for your blog address the other day. I’ll ask him if he got your e-mails, and make sure he contacts you.

Sounds good. I have had a subscriber with the name VilniusJewishLibrary since November or so… just assumed that was he. I know he has my e-mail since he did write as well. You definitely know how to find me, so I’m confident he’ll get to me as well.

Just a clarification regarding my project – the Jewish Community Incubator does have a component that looks back to history, but it does that in the sense that one studies a biography of a historical figure – say, Churchill – not so that you and me can become better Churchill’s, but so that we can learn from his life how we can be better at being you and me, or how to better harness the power of innovation, society and the mind to make our world a better place than we found it.

In other words, history is used as a tool that guides us, and inspires us, but does not proscribe us.

The present is fleeting, passing through time every moment. We can’t control the past, though we can learn from it. The key then is how we learn from the past to impact on the future and in every respect the Jewish Community Incubator is a project that looks forward, and sees each of us as innovators in community building, the same way Tanaaim were innovators in their day. I think that if there’s a misunderstanding about this, I must clarify it. The Jewish Community Incubator is not less a “covenant with the future” than any other idea.

I agree that there is a complimentary aspect to Tsvi Bisk’s proposals and mine, but the “continental divide” between our ideas is along the contour of history. Rather, I think the key difference is in how we look at the past, and how we size up the potential of what we survey to effect positively what we will be as a Nation in the future, and what that means for us as individuals in every respect, as well as members of a community. It seems to me that perhaps in some ways a project like the one I propose is consistent with what Bisk has written in his proposal, and it’s certainly consistent with summaries I’ve read about his book “The Optimistic Jew”. It’s not clear to me though whether I have misunderstood him regarding the role he sees for “Jewishness” per se. It could be that he’d see my proposal, which seeks to define a pan-Jewish identity that utilizes the pursuit of values as a source for establishing common ground for Jewish Community Building, as too much of an echo of Jewish Tradition and Religion to be feasible in the world he envisions. Yet, what I’ve proposed is not in any way “abstract theology”, so perhaps especially the 5th Tier of the Museum of Jewish Activism might meet with his approval. He’ll have to speak for himself.

It seems to me that in the Museum I have done what you described, ARB. Approximately 40% of the floor area of the Museum (which probably isn’t the exactly right term for the building – it’s not really a frontal educational experience or a place that is primarily about presenting history) is on the 5th Tier which is dedicated to highlighting works “social obligations towared humanity” (mitzvot ben adam l’chaveiro) and sparking each Jew to involve himself in similar projects or to initiate his own. I think that seems to be something my idea has in common with Bisks – utilizing social action as a means to cement Jewish identity.

The key difference, though, “is that I am not willing to relate to Judaism as “abstract theology”, or to accept that the weakened “identifying elements” of Jewish identity in “the Jewish past and Jewish tradition” as a terminal diagnosis. I believe that there is a way to turn that around, and believe that all Jews irrespective of stream or lack thereof MUST take ownership over our valuable and rich traditions if we are to retain a semblance as a distinct comunity. I see the opportunities portent in globalization and change as tools in achieving this. I see all this as part of our “visions for a common Jewish future”. I think, though, that we have to understand that the word “vision” is loaded with unstated assumptions about what good communities are, what a good life is, what good is – and I think that in fact we WILL find that they are not “unframed”, but rather completely framed in a Jewish value system. There’s no need to redefine our values, or the word “mitzvah” to mean a project with “universal human consequences”. A mitzvah can be helping an old lady cross the street, not less than ending world hunger. Rather, what’s needed, I feel, is an appreciation that the “unifying force of tradition” is not, if we understand tradition and the possibilities of what I’m proposing for it, something that needs to knuckle under to “real time change’, when in fact if we understand Mordechai Kaplan correctly, it’s precisely that “real time change” that gives tradition its unifying force if only we’d harness its power to encourage this. This is what I was hoping to do with my project.

Dear Tsvi,

In one of your responses on another blog you refer to “practical/actionable projects (modern Mitzvoth) to create a new sense of Jewish identity”, and offer the example

of the Jewish Energy Project. While that is undoubtedly a worthy project, what is

specifically Jewish about it? To paraphrase a wonderful old ad campaign (that most

people on this blog are probably too young to remember), “You don’t need

to be Jewish to love energy independence.”

Stated another way, while Mordecai Kaplan defined Judaism as a civilization

and not just a religion, he later modified his definition to “the evolving religious

civilization of the Jews”. As you know, I am very enthusiastic about New Zionism.

However, I personally struggle with the idea of the specific, particularistic Jewish

content of Jewish civilization. The question we must face in all brutal honesty

is: How will we know that New Zionism is indeed Jewish? Is it realistic to expect

some element of knowledge of Jewish civilization beyond the current need for a project

the “must coincide with world trends and contribute to all of humanity”? Surely the pursuit of the transcendent is an identifiable “world trend”. Can New Zionism stimulate a thoroughly secular appreciation of the insights enshrined in Jewish tradition, while steering clear of both religious fundamentalism and new age vacuousness? Does this fall within the purview of New Zionism, as well as – or inherent in — grand technology projects?

I hasten to add that I consider this a topic to explore for my entire life, specifically within the cultural realm of Zionism. I don’t expect a definitive answer from you

“while standing on one foot”; however, I am most interested in your thoughts.

Sincerely,

Peter Margolis

Dear Peter,

Some great questions and ideas for us to think about in your comment. I’ll leave the heavy lifting to Tsvi, but in the meantime, make sure to see his article published on this blog on energy and Israel, which may begin to address some of your questions. The entry is titled, “Guest Author Tsvi Bisk Asks “What if one billion dollars a year were used to buy Israeli alternative energy technology?”

Here is the link: https://thenewjew.wordpress.com/2007/10/30/guest-author-tsvi-bisk-asks-what-if-one-billion-dollars-a-year-were-used-to-buy-israeli-alternative-energy-technology%e2%80%9d/

Maya

Dear Shai and Peter (as well as Huh!)

I hope this will address your questions – concerns (Shai’s and Peter’s overlap).

1. When you stress ideals (philosophy) over behavior you are giving power to the priests (some Rabbis) – the “experts” whose raison d’etre is to provide “right interpretations. When you stress Mitzvoth (behavior) you are giving power to the people. An act (behavior) is empirical and objective (you see it) – ideals are “idealistic” and subjective (you cannot see them). How do I know what you mean when you advocate an ideal – what does that ideal mean to you? As Elizabeth I said: “I shall not make a window into men’s souls”, meaning that if her Catholic subjects obeyed the common law of the land she could not care less what they believed.

2. The stress on belief it seems to me is Christian; the stress on behavior is Jewish. Re: the famous story of the Yeshiva bocher coming to Rosh Ha’Yeshiva and saying “Rabbi –I am no longer capable of believing in God” and the Rav responding “but what has that have to do with Yiddishkeit?”

3. Yes Peter, ideals are universal, as is humor. But there is a particular Jewish humor, and you know it when you see it. There are Jewish ideals but they are encapsulated in actual behavior not in abstract dissertation. And if these behaviors are copied by non-Jews are they any less Jewish? In any case “Na’Asa vey Nishma”!

4. Serendipity – I am at present reading Soloveitchik’s “Halakhic Man” and although I obviously do not subscribe to the metaphysical underpinnings of his views I instantly identify with his general gestalt. Some quotes: “If you desire an exoteric (not esoteric), democratic religiosity, get thee unto the empirical, earthly life…” and “The thrust of Halakhah is democratic from beginning to end…(it)…declares that any religion that confines itself to some remote corner…to an elite sect… will…(have)…destructive consequences…A religious ideology that fixes boundaries…between people borders on heresy.” To which I say Amen. If the Goyim want to do it too, so what – it doesn’t make anything we do any less Jewish. Indeed it fulfills the teaching to be “A Light unto the Gentiles”.

5. Heschel claimed that every bodily (physical? I paraphrase from memory) function provides us with “spiritual” opportunities – witness the Morning Prayer – can’t get more empirical, or bodily than that. And of course the this world pragmatism of Kaplan does not have to be detailed.

6. I prefer the negative theology of Rambam (and in implication of the entire Jewish tradition) over the positive theology of Christianity and Islam. What God is not – not what he is. “Do not do unto others” and not “do unto others” etc. In this sense our ideals are not: a) vicarious salvation by way of Jesus (the most un-Jewish religious doctrine on earth); b) a prohibition on criticizing Moses (contrary to Muslim attitude towards Mohammed) eliminating jokes about Moses would destroy Jewish humor; c) the passivism of Hinduism and Buddhism and e) the non-democratic nature of Confucianism.

7. Our problem today is how to facilitate access into Jewish identity. Birthright is a good example of how a positive existential meeting with Israeli reality can help do this (90% of the time). Beginning with ideals would hinder this access. Does Birthright per se have certain Birthright ideals? No, they have programs. My proposal suggests projects in addition to programs. The only assumption (not ideal) being that since we will all spend the rest of our lives in the future we had better begin thinking about it and molding it.

8. What is Jewish identity? Well, what is American and Indian identity? A resident of Manhattan, Midwest farmer, Texas oil man, Wyoming rancher and Hollywood producer are as different as different can be – yet they are all instantaneously recognizable as American. They are united by an amorphous meta-identity which includes belief in the American Dream and the Constitution. India is the most diverse country in the world – probably more sub-cultures than the rest of the world combined – yet they are instantly recognizable as Indian and united by their dedication to state building. I believe post-enlightenment Jewry is the same – from Jewish comics to Haredi Rabbis to Jewish intellectuals, we know what a Jew is when we see one. The question is what will unite us as a people – I believe only practical mitzvoth relating to the questions disturbing the entire human race.

9. Jewish culture is never as dynamic as when it is touching the nerve endings of the general human condition. This is the eternal truth of Jewish history – from antiquity when the Hebrew community discovered Monotheism to the Enlightenment, when Jews as individuals made discoveries, had insights and created ways of economic and social interaction that changed the course of civilization. How is it that this numerically insignificant people has had and still has such an impact on society at large? How is it that one hundredth of one percent of the human race produces 30% of its Nobel Prize winners? Why is it that a country smaller than New Jersey in area and population preoccupies the world to the degree that it does? The answer I believe lies in a Jewish attitude towards life that is beyond doctrine or tradition. An attitude that is more sociological and psychological than philosophical. All Eastern philosophy and much of Western philosophy have been concerned with achieving equanimity, composure and tranquility in the face of the absurdity of existence. The Jews, on the other hand, seem to thrive in an attitude of never-ending dissatisfaction. We are never content; we are always looking for new ways to do things, to correct things (Tikkun Olam). More than the people of the book we are the people of the eternal question. “Why?” and “why not?” are our two guiding lights! We are the people who constantly question God, challenge God and wrestle with God. It is our never-ending questioning and challenging that has produced our contribution to humanity at large. It has also made us what we are – Jews!

The beauty of my idea (how immodest) is its flexibility and portability. And here I would like to clarify my target audience:

1. Every Birthright graduate and potential participant is a candidate for a Covenant with the Future Program in Israel as well as Covenant with the Future programs and projects in the Diaspora.

2. Every Masa program is a framework for Covenant with the Future components

3. Synagogues, Jewish Day Schools, Jewish Studies Programs, youth movements can all have Covenant with the Future programs and projects

4. Could be very attractive for the new Internet based Jewish developments (such as Ariel Berry’s for example)

5. Most important the program could be a great Jewish example of “blue ocean” marketing – attracting an entirely new Jewish constituency (1,2,3 being “red ocean” marketing – appealing to existing constituencies)

Covenant with the Future has four components:

a. Theory: The future is a more imperative concern for Jewish survival than the past

b. Experience: meeting with High Tech Israel

c. Practice: Diaspora projects like the Jewish Energy Project.

d. Intellectual: a Jewish Philosophy of the Future (based as much as possible on the sources)

If we cannot strengthen Jewish identity with these four then I doubt we can do it at all.

Tsvi, hi

1 and 2. With a history as long and as rich as that of the Jews, anything we say as it turns out must have one time been true. It’s like the old joke about the rabbi deciding on whether the husband or wife are right in a dispute, and the rabbi said they were both right. They asked how it can be so that both can be right, and he replied, “your both right about that, too”.

I think your view of rabbis and “experts” and what you call their “raison d’etre” unnecessarily places them in one camp (those who we give power to by considering that there are “ideals”), and everyone else in another. Your response sets up an artificial binary choice, when in fact there is a full continuum of responses to ideals and behavior in Jewish culture. I stress that this provides a broad enough tent to include everyone, rather than viewing this as a power play between the “magisteriate” and we common folk. It’s just not necessary to accept that situation as being the rules of the game. We can change the rules.

For further guidance, I suggest Professor Menachem Kellner’s book “Must a Jew Believe Anything”. It is a good primer of exactly the issues you raised in your response. There, Kellner proves that today’s orthodox approach to Judaism (the belief that beliefs must be “correct” for you to be Jewish) began with Rambam, who suggested that Jews are defined by their beliefs – 13 of them, actually. Rambam was the first major torah commentator to propose the existence of a “church of believers”. Yet notably, the 13 “ikkarim” only became accepted by a broad cross section of Jews in the 16th Century, 3 to 4 centuries after Rambam died, with the standardization of Jewish practice and Rabbi Karo’s Shulchan Aruch (approx. 1590 CE). Before the 1200’s then, you are right – it was more about what you did, than why you did it. By the 17th Century, belief became a hallmark of Jewishness and it has been that way since. It’s not a reflection of authenticity, but is rather proof of flexibility. Also useful is Marc Shapiro’s “Limits of Orthodox Theology”.

To my mind you are too quick to make light of this flexibility. Jews and Jewishness need not either be philosophically based (ideals) or behaviorally based (deeds), it is certainly both, and ideals need not be considered only in a religious context to be considered “Jewish”. Proof of this is the vast contributions of non-rabbinic Jews since the time of the Emancipation to Jewish thought, from Spinoza to Fromm. I think that Peter Margolis’ question is spot on – can we find a way to gain the insights from Jewish tradition while steering clear of the religious fundamentalism and new age vacuousness? I think that’s what we have to do.

3. I am not using the word “ideal”, but rather “Jewish values” in my proposal – I wonder if we mean the same thing by these words. If you mean what I do, I intensely disagree with you regarding whether relating to “ideals” is divisive and a hindrance. I also use the phrase “Jewish moral intelligence”, and stress that the observation that ideals are “universal” is not very useful. To make your point, it’s HOW we DO those ideals that defines whether what we’ve done and our motivation for doing it is “Jewish”. It’s the HOW that concerns us, not their “universality”. At the same time, I don’t think that it is productive to use the “duck test” to define Jewish ideals, excusing the process as an “abstract dissertation”. It is exactly the practical nature of the HOW that gives universal values their Jewish flavor, and our communities their Jewish character, and it is precisely on this point that I hope to “incubate” Jewish communities by providing a context for learning the vocabulary of our values again. In a sense, the process is not different from that of the Pesach ritual dinner, where we learn about our national narrative. I am using narratives from historical writings and history to teach the Jewish approach to ideals, so that they are not abstract and are rather concrete and solidly based on actual projects and personal missions that can be emulated.

Regarding your last very interesting point, if the behaviors are copied by non Jews are they any less Jewish? Good question. I have often observed that the Protestant covenantal approach of the “founding fathers” in America has made America a more Jewish state in some ways than Israel is. But I’m not sure if beyond that observation the question is all that useful, since what’s really at issue here is whether what WE as Jews are doing is “Jewish”.

4. R. Soloveitchik’s approach here is essentially the same rationalistic approach as the Rambam’s. I suggest “The Living Covenant” by Rabbi David Hartman for an interesting comparison between R. Soloveitchik, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, the Rambam and Hartman’s own views on the matter of what the purpose of mitzvot are. It’s also important to examine these in the context of the two conflicting approaches of “homo religiousus”, which is the Chassidic approach, and “halachic man”, which is the Brisker approach. These two approaches have been fighting it out since the Middle Ages – the approach of homo religiousus actually predated and coincided with the time of the Rambam (Nachmanides, R. Yehuda Halevi, etc.), who it has been argued was Judaism’s first modern orthodox rabbi.

R. Hartman’s book “Conflicting Visions” is a good follow up on your reading because his views regarding R. Soloveitchik and the passage you quoted become clearer when the matter of Soloveitchik’s opposition to interaction between the orthodox and non-orthodox rabbinate is examined – it seems that indeed his was an “ideology that fixes boundaries between people”. But all that said, I don’t understand what point you were addressing in your response.

5. Heschel’s view you mentioned is the same as Soloveitchik’s (the idea that we bring heaven down to earth). But all that said, I don’t understand what point you were addressing in your response.

6. You’ve made a huge leap between the Rambam’s approach to G-d and our approach to our behavior within Jewish contexts. Rambam states his belief that the idea of G-d is so incomparable to anything we know that at best we can only speak of what G-d is not. The reason he does this is because of the UNIQUE nature of G-d, and certainly then, G-d being unique, there would be no implication from this that could be applied to the entirety of Jewish tradition, as that tradition shares nothing in common with G-d, per se. We have no problem describing Jewish tradition accurately.

7. I think that we mean different things when we say “facilitate Jewish identity”. I think that many “programs” and “projects” are building on a latent sense of Jewish identity in the participants. But when that sense of identity has washed away, or has been laced with ambivalence, what do these “programs and projects” really offer? What will happen when all we have is programs and projects, but no real sense of community? Can we sustain ourselves? I think not. That prognosis is happening today, all over the world – not just in the Jewish community. I think we “programs and projects” are an appropriate tool, but they don’t by themselves have the power to achieve and sustain “community”. To do that, like it or not, we need to come up with some way to deal with the question Peter Margolis asked, in my opinion.

8. I think you and I agree regarding the value of “practical mitzvoth”. I think we differ on the definition and the reasons. First, “mitzvot” comes from the word “tzav”, or “command”. It is necessary to be clear that Jewishness entails a sense of “obligation” (dismissing that concept for the moment from a theological sense of obligation) that sees our positive actions in the world as a “command”, not merely a voluntary matter. I sense fromyour writing that you see it more as volunteerism. If not, how do you propose to inculcate a sense of “obligation” in your proposal? Second, regarding scope, I don’t think “Jewish values” sees anything special about the entire human race that is not also special about each human being, even without inserting a “question”. The reasons I say this I think underscores the value of studying “ideals” in building “projects and programs” that are “Jewish”. I’ve said before, helping a little old lady (or a big one, or a man) across the street is not less a “practical mitzvah” according to the “ideals” I think we should be teaching as a community. I don’t understand why you are so antagonistic to the idea of “ideals” (well, actually I suspect you feel they are coercive – but they don’t need to be).

9. I really liked your response here, your observation about our national “edginess”. I do think, though, that you are too sanguine regarding your view that “Jewish attitudes toward life is beyond doctrine or tradition. An attitude that is more sociological and psychological than philosophical”. It is precisely THAT Jews do not reach their edginess by being naval-gazers that typifies us as a culture. But we do reach it, and the way we do it is through a process of national story-telling and cultural devices that continually allow the “message’ of what we are to be passed from generation to generation. I think it’s quite improbable that these messages can be passed on with ‘projects and programs”. You and me and everyone we know who is “Jewish” picked up their Jewishness from the previous generation and from our environment. But when they die, when we die, when our environment changes, when we become convinced that our values are “universal” and “Judeo-Christian” and there is no difference between us and others, on what basis entertain the prospect that what we are will continue?

I think it’s worth examining your “four components” from a causal standpoint – which are prerequisites for the others? I’d claim that d, “A Jewish Philosophy of the Future based as much as possible on the sources” gives rise to a, b and c. Without it, I also wonder whether “we can do it at all”.

Dear Shai,

I do not disagree with any of your historical analysis. I simply claim that nothing you wrote will impell an alienated young Jew to get involved in Jewish life. Certainly not throwing sources at him (Rambam or Hartman). Once you have him involved in a project you MIGHT be able to talk to him about the other stuff, but you cannot make talking about the other stuff a condition for taking part in the project else you will have defeated your purposes.

What is Jewish community? How about what are Jewish communities? Well to paraphrase a very famous book “they are what they are”. Who am I (or anyone else) to dictate what a Jewish community is?

You say you are not sure we mean the same thing when we talk about ideals — here you make my point. “I believe in justice” — “I believe in justice too” So what is justice for you and what is it for me? An act is observable (even measurable) — it is objective and empirical.

We do agree that there is a latent sense of Jewish identity that can be appealed to even amongst most alienated Jews. I have often said that there are many Jews just looking for an excuse to be Jewish — but havn’t yet found it.

My impression of the “big idea” concept was not to get into philosophical discussions about the essence of Jewish identity (which as I point our in my book is evolutinary in any case)but to develop a concept that would enable as many Jews as possible to find that excuse to be Jewish (Jewishly involved if you prefer). As for unifying ideals — ours are fundementally negative — we do not believe in vicareous salvation (Jesus); we do not believe it is forbidden to criticize our prophets (Mohammed); we are not passive (Hinduism and Buddhism); and we do not believe in a heirarchal social system (Confucianism) — we also do not believe the world to come is more important than this world.

Throw a positive ideal at a room of Jews and they will chew it to bits and start yelling at them — throw a project at them that is self-evidently beneficial and they will immediately begin discussing how to implement it.

Will my approach guarantee the future of the Jewish people? How the hell do I know? I was not aware that that was the question on the table (if it was I would not have participated in the contest). Will my approach give us a chance to reinvent ourselves in the future (chance not guarantee)? I believe so.

All the best,

Tsvi

Dear Shai,

I am enjoying this exchange and appreciate the time you are taking. But I get the feeling we are on different wave lengths and talking past one another. Perhaps when we meet we will find some common ground.

I also write about Jewish identity in the 21st century, but I essentially believe that what we DO is our common identity; what we think is our private identity. I find much of present Jewish life tiresome (including a certain obsessive pre-ocupation with the past). Just because it was doesn’t make it Jewish culture — Jewish culture is not a museum piece — Jewish culture is what we are and doing right now. I teach history. I love history (especially ours). I believe we must learn it, respect it, draw lessons from it, celebrate it (all our holidays are celebrations of the past) but we must not idolatrize it. As Kaplan says (and JFK also said) the past has a voice not a veto. But even that voice will not be heard if we do not get Jews involved in some activity.

Warmly,

Tsvi

Tsvi, hi

I think we’re getting somewhere – I’m understanding where you’re coming from but I think you’re not reading me right. We agree it seems about the historical analysis. I find a refusal to define something as essential as “Jewish community” as problematic. I define community using Lawrence Haworth’s words in his book, The Good City (which I recommend). “A group of people make up a community insofar as they join together in valuing something. The common vaue that unites them may be a goal they all consider worth achieving, so that each, by noticing the identiy of his objective with that of the others, develops a sense of kinship with them. Or the common value may be a memory they share, a sense of common past that they unite in regarding as precious” He goes on with similar types of descriptions, but they all require holding in common some unifying value. I picked Jewish values as that common thread because I think it has the power to unify all Jews across the entire spectrum of identity.

But, that said, I am not proposing “throwing sources” at anybody to get him involved in “Jewish life”. In the context I used them, the sources had their value as a response to you, not them. I most certainly don’t think the sources in the sense you seem to mean it is in any way a precondition for anything. And I think that what you said about “throwing a positive ideal into a room and Jews will chew it to bits and start yelling at them” (you’re observing the same thing that von Hayek did – that people find it easier to agree about what they disagree about) is actually a cultural flaw to be repaired to the degree it exists – it’s hardly a reason to turn tail and walk away, just because other options might be easier. I am an orthodox Jew and I feel absolutely no need to force people who think like you to be like me at all. I am not as alone in believing this as you seem to sense. Too much is at stake, I feel for me to be otherwise.

What you call “philosophy” is I think much more practical than you seem to. I don’t see it as abstract.

I’ll give you a few examples of what I mean. On the 3rd Tier of my proposal (Second Temple to Emancipation Period), you’d come across a quote by Zechariah, “The world rests on three things, on Justice, on Truth and on Peace”. Or in the 2nd Tier (First Temple to Second Temple Period) you’d come across a quote by Isaiah, “This is my chosen fast, to loosen all bonds that bind men unfairly, to let the oppressed go free, to break every yoke. Share your bread with the hungry, take the homeless into your home, clothe the naked when you see him, do not turn away from people in need. Then cleansing light will break forth like the dawn and your wounds shall soon be healed”. Now, you and me can figure this out without the Rambam and Hartman and the rest. It’s not rocket science, it’s inspired – it’s something I’m proud of as a Jew, and I suspect you are, too. And about these beliefs there is nothing of the “negative” you asserted – these are affirmative beliefs of Jews, these prophets asserted.

But these values, as great as they are, and as much as we share them and hold them with other nations and religions, the words themselves are not the whole story. In the end you are right – it’s about what we DO with them.

What do you do, for example, when you have to choose between Justice and Peace, or Truth and Justice? Or your question, what’s justice for you, and what is it for me? And, what if you have to choose between clothing your own children or the other person’s children? What do you do if you suspect a “poor person” is conning you? Each of us is capable of those decisions, but I think we have to admit that most of us are torn by these conflicts. And so have Jews throughout the generations, and they wrote about it. That some were rabbis does not mean that a person suspicious of the rabbinate today has nothing to learn from them. We still read Aristotle even though some of his ideas turned out to be verifiably wrong. From the time the prophets spoke these words until today, libraries were filled by people who saw these words as practically relevant to their everyday lives. How is today much different? Are there no poor people? Is everyone living in a just society where nobody lies?

I claim to you, Tsvi, that “Jewish values” lay in those conflicts. It exists in the combat over the ideal of what life is and how we should live it, and the world as we actually confront it. Traditionally, this process of exposing yourself to the arguments is called “talmud torah” but it’s more a lifestyle than it is a prediliction for philosophy. It’s more related to applied ethics than it is to existentialism, for example. I assert there is a Jewish cultural approach to this that can occur outside Bnei Brak. It’s about grasping life by both horns and refusing to let go of either when you have to make a choice. It’s about being honest about the conflicts and of our lack of certainty about what’s right. Anybody can do that, not just scholars.

This populist approach and the embrace of personal authority is, I claim, is what gives us Jews as a community the “edginess” you referred to, and merely engaging in projects and programs can’t achieve that. The reason I believe that is that projects and programs, if they are not overlaid by a system of common values, only have the power to enrich an individual – they have no power to bind you to me or me to you if our motivations for achieving the goals of our program are unique to you and me.

Edginess is a trait that has its habitat in Jewish communities, Tsvi, and if we focus only on the programs and projects, achieving only great things but not conveying the ta’am (taste) of why we seek to achieve these things vs. different things, then we do not avail ourselves of the potential for personal growth that is inherent in a life so lived. Ideals are needed so that the message of why we do what we do can enrich us. At least that’s what I’m claiming, I think with evidence.

I am not claiming for you that the rabbis in my scenario have any more claim on teh truth than you or me. This is not an appeal to authority, it’s an appeal to you and me and to all Jews to grasp onto our culture and claim it for themselves, to not allow only a small part of us or even teh past to dictate what Judaism will be and mean for us. But for this desire to go beyond a mere claim, it requires heavy lifting – an answer to the questions Peter asked in his comment. I feel I’m answering those questions head on, about how it is that we can achieve Jewish community by all of us, regardless of stream or lack thereof, tying into our special way of living – our concern for what’s right, and using our community contexts as a tool for personal growth.

Now to achieve this we have to have communities that are influenceable, the same way that we are influenceable by them. There is the matter of who has access and under what terms. There’s the matter of the efficiency of our efforts – and other issues to be addressed. But I don’t see these as “philosophical” issues at all. You seem to. You are an American citizen, as I am. Are you like me, in that you are unable to imagine what America would be without the ideals of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, documents that by the way draw heavily from concepts built up in the Tanach? What kind of America would America be if its leaders could only speak of tax policy and health care, and not about the pursuit of happiness or all men being created equal?

Indeed, it is a whole philosophy behind those discussions, not unlike the kinds that accompany the building of any society (Jewish included) and our own moral intelligence, informed by our Jewish culture, has much to say about those things that can make our lives as Jews within Jewish communities much richer and meaningful. But we can’t be passive, and I believe that fine-thinking people such as yourself need to put the connotations of religion and the rabbinate behind you, and claim your right to your turf based on Jewish values, even if this means you plant your flagstaff on the territory of people who feel you’re not entitled to do so. It’s yours as much as mine and theirs. It requires courage, but for the sake of our communities and what we as individuals gain from community, we must do it. Then, as you say, perhaps in the competition of ideas more Jews might consider other options within a stream within Judaism, but nobody can move the boat without an oar, and I believe our ideas have to provide it.

Your perspective that Jewish identity is evolutionary was also an observation of Mordechai Kaplan’s – but that it is so is, I feel, beside the point. Kaplan’s observation was not prescriptive as Big Idea’s are – he was not, as far as I know, proposing that we change the meaning of Jewishness simply by redefining it – but rather was speaking of a process that no single idea or program or project, or even a series of them, controls. It’s organic – not in our hands. Your approch in your idea is I think rightfully practical – but I wonder if your linking identity with participation in projects addresses the values issues I raised as critical to building a community from us – not just people who get together to achieve a common goal, and who dissipate when the goal’s achieved. Isn’t this a redefinition of Judaism? I’m just asking, why rewrite the bylaws? Bahai is only 100 years old or so – they pretty much beat us all to the finish line if projects are the ikkar – so if we distill the question then to what’s left of it, it’s about What is the Jewish People and Is there anything in it for me to be Jewish?

I think that your idea is an excellent one in the context of strong Jewish communities, where people are not merely looking for an excuse to be Jewish but are looking for real actionable expressions of their values that enrich them as people and provide their lives with meaning and purposefulness. I think that communities provide the context for those actions to congeal around “meaning”. I assert communities are factories for producing purposefulness. I think that without communities, projects and programs will achieve their own goals, but this will not have enough power in it to sustain the communities that affix meaning to our deeds.

I don’t disagree with what you said in your last post. I am not so sure we’re on different wavelengths – I do think we actually disagree becaues I do believe what we think has its public manifestation, and I point to the quote from Lawrence Haworth as a representation of how I feel about that. But I’d love to meet. You’ve got my number, so let’s get in contact.

Shai

Dear Shai,

I don’t disagree with what you have said, but you are not going to be able to say anything to anybody until you get them in the same room. You are Red Ocean Marketing (talking to people already involved in Jewish life). I am Blue Ocean Marketing (trying to attract an entirely new constituency).

Moreover, the ideals you cite in your next to last communication are universal ideals that incubated within Jewish culture — does that make them any less a Jewish ideal? Can we not convey a Jewish ideal of “Tikkun Olam” by way of the Jewish Energy Project better than citing references about “Tikkun Olam”? Is not “Na’Asa vey Nishma” a Jewish ideal? Isaiah is quoted on the Liberty Bell; the leaders of the English Peasants Revolt in the 14th century quoted Bible (I paraphrase) “We are all descendents of Adam and Eve, are we not therefore all brothers and sisters — so why should some be more privalged than others?” “We are all made in the image of God and are therefore equal in the eyes of God — why should we not be equal before the laws of man?” That these ideas melded in nicely with English cultural developments since Common Law and Magna Carta is a good example of serendipity. They certainly did not take root in Germany.Are these Jewish ideas? Or is constitutionalism per se a consequence of a convergence of various cultures (including to be sure our own)?

How are you going to get people to your Museum and instill them with the sublime ideas you have unless and until they are already Jewishly active? And how is it to relate to their future lives?

The central problem for me is how to enable young Jews to envision themselves in a human future in which they are still Jews! Or as Bronfman said “Why be Jewish?” You are Orthodox, so the very question must seem to you (personally) as irrelevant. I am secular and have a much more difficult job in answering that question (despite over 30 years of being a professional Jewish intellectual). I have to constantly reinvent an answer — this I can only do through activity, not meditating on our rich cultural past. I must fantasize a Romance with the Jewish future rather than conduct a love affair with the Jewish past.

Tsvi

The “same room” you describe is what I propose to build in my project.

I continue not to understand why you think I’m proposing meditating on our past. I am doing this only to the degree that your students sit in your classroom and listen to you discuss the past. How do you think about the future? By learnign from the past – that is why you teach History, I presume, Tsvi, right? You look for patterns, cause and effect, motivations, results. I’m proposing doing the same thing. So I don’t understand why you keep claiming that I’m doing anything with my idea that is different from what you do in that regard in your classroom.

I wish to reiterate that I am not saying that projects and programs of the sort you propose are bad, because in fact I believe they are good. What I am saying is that they are and always will be insufficient to the task of sustaining Jewish communities if we do not have these communities as contexts to frame the meaning of those projects and programs. Programs are buying the fish. Communities are teaching to fish. That’s my point.

I’m saying that yes, do your energy project. But if you want your project to have the power to build Jewish communities, give the particpants some Jewish”angle” to latch onto. Show them how their acts are sanctioned by their community, and how their acts make them a part of that community. For instance, mention as the Midrash Rabba related to the teaching that we only get one earth and not to destroy it, and the proper meaning of the word “v’chivshuha”, which is interpreted wrongly as “subdue” when it means “steward” in the phrase “multiply and subdue the earth”. Compare these values to values like housing. For example – I worked in places where farmland was destroyed for housing projects. We tried to cluster the houses so that as much of the open space was saved as possible, and that’s a value. But there’s a competing value that people need affordable housing. If I started a project to provide affordable housing, certainly I would run across competing values like these, right? What tools do we give to help decide wehre we come down on this issues?

Teach people our culture’s values with regard to these things. Don’t force them to search it out in ashrams or in teepees – people are looking for meaning, Tsvi, but we’re not giving it to them.

If you suspect that all I’m interested in is giving quotes, then you’re misunderstanding me. If I thought that’s what I was doing, I’d also be skeptical. Rather, the point of the whole project is to encourage the development of a communal framework for performing our societal obligations to others.

A large part of the project (30%, the 5th tier) is geared to showcasing actual examples of real people engaged in Jewish Values projects around the world, whether it be paper recycling or rescuing animals or helping orphans – all so that every attendant who visits can find that his community wishes to inspire him to get involved with his own personal life mission – to examine his skills and strengths, and what pisses him off, and to get started fixing it using the values and mores of his community. B’gadol it also gives a sense of what Jewish values are, by providing examples – you’re right – not everyone can absorb the messages and philosophy, especially those first exposed to it and younger children. I leave it ot others to speak to the religious issues (halacha) – I’m proposing the doing of good deeds as the cultural manifestation of Jewishness, the substance of Jewishness, and I leave it to each Jew to decide how much of the “form” of ritual and the like they wish to take upon themselves in a different venue. That’s not the purpose of my project, and I don’t even bring it up. You keep calling these ideas “abstract” and “sublime” and it leads me to believe that you don’t really grasp what I’m proposing. It is hard core action, not less than what you’re proposing. THe difference is that I’m claiming that there are ideas behind our actions that, when we are aware of them and they are held in common, bind me to you and you to me so that we form a “community”. WIthout community, I claim that we (any human, not just Jews) cannot fully develop as a human being – we will remain selfish and self concerned, unable to manufacture meaning or purpose from our brief span on this earth.

Most of the people I encounter every day are secular Jews. That said, they’d be insulted if I claimed they were not “Jewishly active” even though they are not religioiusly observant. I told one of them when I described my project, when he told me the “shtreimilachim” will have a hard time with it, that I am unwilling to turn my back on him or any Jew for the sake of satisfying religious purists. If Judaism cannot be for all of us, it’s for none of us, MK Melchior often says, and I agree with him. I feel that there is room for us all in a tent built with these ideas.

Especially for those who have children, they are looking for a way to teach them proper comportment and values. The schools, the television, frequently families, the neighborhood – all offer pieces of “values” but most of what these offer is confused, unfocused and hedged. I’d of course take the examples you give and teach those, too.

I divide the unaffiliated into two groups, and you seem to see them as one monolith. There is a group of unaffiliated people who are simply open minded enough to consider any potential source of personal growth, from wherever it comes. That it comes from their own inherited culture is a bonus. Then there are those who are unaffiliated and will not become affiliated based on the pure speculative benefit of what communities offer. They need proof. If/when the ideas I propose are implemented, and if they are successful, slowly yet surely I predict these Jews will affiliate with communities, too. Why shouldn’t they?

The point you keep referring to, and I keep rebutting, is in essence “what is a Jewish value”. I respond that the universal values you refer to is not at all what I am focusing on. I’m not denying these values have universality. But what is harder to grasp is what affirmatively I’m propsoing.

Mine is a hard concept to grasp perhaps because I’m proposing a new way of looking at values than you, or orthodox people, are used to. When I ask myself what “Jewish values” are, I also am aware that other cultures share the Tanach. And the equivalent of “do unto others…” is common in many cultures, not just those the 3 that are Judaism and its derivatives. Rather, what I am not being clear enough about apparently is that it’s the WAY we live these values that I am promoting. I am asserting that this WAY we live the values is uniquely Jewish. There is a WAY that we engage in life, informed by our national story and culture and literature, that informs how we behave as Jews and communities. But that vocabulary and heritage is rarely taught. Instead, we learn history, ritual, rote memorization – we don’t properly expose ourselves to the essence and substance of what all this can MEAN to us. And without that, of course few would see the relevance to our lives.

I get into this in some detail in my responses to the comments on my project, and I direct you there for further reading so as not to rewrite it all.

I’d like to know why you think it was “serendipity” that caused common law and Protestant state governments to be congruous with Tanach concepts. My sources for my statement are the half of Hobbes Leviathan that is rarely published (it’s a commentary on the Bible essentially), amongst the Dutch it was studies like Petrus Cunaeus’ “The Hebrew Republic”. You’ll find excellent articles proving my point in the Journal of Hebraic Political Studies such as Strumia’s “Ancient Republics in 17th Century England and the Origns of the MOdern Dichotomy Between Authority and Power”, or Bartolucci’s “The Influence of Carlo Signoi’s De Republica Hebraeorum on Hugo Grotius’ De republica Emendada”. Perhaps the most comprehensive article proving the point is Yoram Hazony’s “Judaism and the Modern State”, which you can download from http://www.azure.org.il (Summer 2005 – Azure Magazine).

I’m all tuckered out – I think it’d be best that we meet. Perhaps with Maya and the other Israeli participant, R. Morey Schwartz? I think it’d be fun to debate these ideas in person.

I had a good night’s rest. My friend told me I need to come up with a way to describe my approach in one or two sentences and with the help of these talkbacks and the responses, I think last night it came to me.

“I am proposing “societal obligations to people” (aka mitzvot ben adam l’chaveiro) as a “lifestyle choice” that we as Jews collectively take upon ourselves as a communal value, and as a means to finding meaning in life and gaining a sense of purposefulness. The Jewish Community Incubator is designed to realign Jewish identity and institutions around this objective by creating a distribution network for the cultural wisdom, lifestyles and means for achieving this goal.”

The essential difference between our aproaches seems to be that your believe that the “means for achieving this goal” is the ikkar, and I believe that we need “cultural wisdom, lifestyle” and institutions to achieve “community” in any sustainable form. When I refer to “wisdom”, this has connotations for you that it doesn’t have for me because of the political context in Israel within which “wisdom” is defined and distributed. In the institution I want to build, the definition is broader and the “intake” of the wisdom is not coerced, but rather completely and wholly selected in whole or in part by those who are exposed to it. The the whole point of “free choice” that makes living valuable would be undermined if I made the process authoritative – I want it to be a learning experience and iterative, like life experiences are. By doing this, I think that Jewish communities can become more creative in producing associations with our culture that are enriching.

Dear Shai,

1. Serendipity because the English example is before the Reformation and until the 14th century made no biblical reference. All your examples (very good ones) are post Reformation and in various degrees were greatly influenced by the biblical gestalt.

2. I agree that once they are in the project we could Judaize the activity with proper references.– but references without activity is barren, while activity even without references is still of value. Na’Asa vey Nishma!

COMMUNITY —

This is what has been bothering me about your approach. You confound identity with community. I have no need of “community”. Indeed I hardly know what it means. My experience with social entities that might be described as community — kibbutz, settlements, Haradim, small town America — have been dark and off-putting (the post crisis Kibbutz is much more attractive to me then the classic kibbutz).

I have friends, colleagues, neighbors and acquantainces (real live persons). I also am a citizen of organized societies (Kfar Saba, Israel etc.) This is all I need or want. They all are liberating for me — widen my options as a human person. Being part of a community would limit me. Why should I want to be bound by communally held values? Why would I want to limit my freedom of action by committing to an abstraction (that no one has yet defined to my satisfaction)?

My friends I know and can define; organized society exists objectively — I can see it and measure (qualitatviely as well as quantitatively) its functioning. For the rest, belonging to the human race by way of that segment of humanity called Jewry is quite enough for me.

By the way, what ideals and whose ideals? Gush Emunim or Peace Now? Buber’s or Kahana’s?

I will allow for the sake of the argument that within Jewry there are communities — from Bnai Brak to the Kibbutz — I don’t belong to any of them and feel no need/requirement to do so in order to feel part of the Jewish people.

Your aim is Jewish community. My aim is to attract individuals to Jewish peoplehood by enabling them to self-actualize within Jewish frameworks (Jewish because Jews are doing it) not to attract them to community. If some individuals want community — fine, but it is none of my business.

My expereince is that communities with common ideals and values are close-minded, often intolerant of non-conformity (a Jewish value to my mind) and in general oppressive. They view education as a means to indoctrinate the young with their values rather than to develop critical thinking. Indeed critical thinking in such communities is often teated as a kind of treason (treif). Thinking for yourself is considered arrogant and egoistical — “Thats not the way we do things around here”.

Freedom and community are mutually exclusive. The intellectually curious almost always gravitate to giant urban centers (you know, those bastiions of alienation).

Could you gvie me an example of some ideals that are exclusively Jewish and around which you could organize a community of critical thinkers? If so you might convince me to change my mind.

Warmly,

Tsvi Bisk

Thanks for your response, Tsvi.

British covenentalism established itself in the 1700’s, but was already gaining form in the late 1600’s. Then, it disappeared and things went off mostly as they were before, and the real beneficiaries of that thinking were the colonies of what became the United States.

Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks recently wrote a book, which I finished reading on Shabbat, about rebuilding society that looks to these “covenental” democracies as modern day manifestations of the biblical ideals – he suggested that Britain would be stronger as a nation if it sought to establish a national narrative and revisit the British theorizing of the 1700’s (Locke, Milton, etc.). This is because R. Sacks sees in the biblical political model an ideal. He interprets the selection of a King during the life of the prophet Samuel, and the seeming disgust with which this idea was received by G-d, not as a disaproval of monarchy but a warning that taking upon ourselves governance is at the cost of some of our personal sovereignty. Nevertheless, that choice can be a good one, if checks and balances are in place to ensure that the government works for teh people, and not the reverse. Too bad that in actuality, most Jewish governments after the monarchy was established seem to have given anarchists more fodder for their views than communitarians for theirs, but the point I was making was that the comparison and contrast of choices by theorists of governance during the formative stage of England after the Industrial Revolution (as opposed to the Reformation) were inspired by the biblical model. Generally, if you want to permit yourself to believe that religious people are not indoctrinated automotons, Rabbi Sacks would be a good author to familiarize yourself with. Also Rabbi Hartman, who I mentioned in a previous comment – and there are many, many others. Bnei Brak and Mea Shearim have what to offer, but they do not own the franchise on Judaism, Tsvi. You own it not less, but I think what we are talking about here is whether you, and those who think like you, think Judaism has something that can be valued as well as owned. I think it does, and if you don’t, I hope to convince you and those who think like you that it does (to be clear, I am referring to a cultural approach to Judaism and I leave the ritual appetite of Jews to the existing streams – this is not the purpose of my project to deal with those).

I’m not speaking of a political polity when I speak of “community”. I am speaking of a voluntary association that requires in return a sense of obligation. I’m not speaking of an association like a military that people act within for the sake of community without volunteering, even though they in some ways benefit from that association, I’m speaking of communities of people who share common objectives regarding what their lives should achieve to be “meaningful”. I don’t think the examples of a Kibbutz, or Bnai Brak, or Gush Emunim, or Peace Now, or Buber, or Kahana are paradigms. I think the paradigm of what I’m speaking of has its source much, much earlier, especially in the words of prophets like Isaiah, Micha, Amos, Hoshea and the like.

I don’t think we mean by “community” the same thing, nor do I think we share the same vision of what potential communities have as contexts for personal growth. By community, I mean what Lawrence Haworth meant, and I quoted him in my comment of January 17th, 5:40 pm, first paragraph. What you call community is something you see as coercive. Some communities are, but I’d call them “bad”communities as opposed to “good” communities – and so does, not coincidentally, Lawrence Haworth whose ideas I draw from liberally and with whose thought I intensely admire. If I wasn’t clear, I’m looking to make of Jewish communities “good” communities.

Coercion, however, still remains an element of all socieities with laws, and you can’t escape the fact that even if your community is not coercive, your society will be to so to at least the extent necessary to protect people from the “tyranny of the majority”.